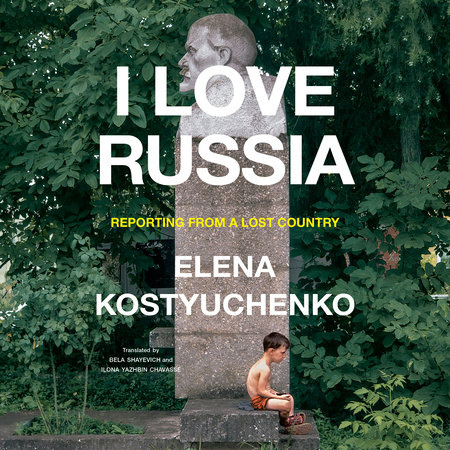

She cares that her «beloved country» does not disappear: thoughts on the presentation of Elena Kostyuchenko’s book «I love Russia. Reporting from a lost country»

I was at the book presentation by Russian journalist Eelena Kostyuchenko, “I Love Russia. Reporting from the lost country”. I did not hear anything extraordinary, something that Ukrainian or foreign journalists would not have already said. And yet, there was a packed room at the presentation; people admired her, applauded, and stood in line to talk after the event.

I wanted to voice my questions publicly, but there needed to be more time. I had to ask them privately. I didn’t hear anything new, anything I had not known before (before the presentation, I had watched several interviews with this journalist).

On my way home, I constantly asked myself:

“Why is this journalist and what she will say so important to people? Why, even though she says things that everyone already knows, is she still considered extraordinary? Why do educated people come to her defense and write that she is a great person?

Is it just because she is Russian? So does this mean the world still cannot eliminate the imperial narrative about “great and important Russia” and “the most crucial voice of Russians”? Is this journalist being listened to precisely because she is from the metropolis and not from some “outskirts” like Ukraine, Kazakhstan, or Georgia? Would these people come to a meeting with Yevhen Shyshatsky, who wrote the book “Journey to the Beyond. Mariupol” about how he, a Ukrainian journalist, tried to break into the occupied city to save his mother?

These questions devastated me so much. I don’t want it to be true just because she is Russian, and Russia is used to being listened to. And thoughts about the victory of the film about Navalny at the Oscars and, in general, sentiments towards Navalny, even despite all the terrible colonial and pro-Kremlin narratives that he and his team spread (I will remind you that there was Volkov who wrote that the dam of the Kakhovskaya HPP is somehow exploded on its own, and Navalny compared Crimea to a sandwich) devastate me even more.

I love russia…

But let’s return to the presentation of the book and its author.

A conversation began about the title of the book. Elena said that love for Russia is what she feels; it is a feeling of belonging to people with a common difficult fate. And she wants to oppose her vision of what it is to love Russia, and not what Putin says, that if you love Russia, go and fight, kill. And she is aware that the name causes resonance and rejection among many.

Elena calls a war as a war, talks about fascism in Russia, admits the war crimes of the Russians in Ukraine, confirms that the Russians were in the Donbas and Crimea, talks about the multi-nationality of Russia, talks about her own sense of responsibility that she did not do more when she could, that she did not noticed what her state was turning into, that she was simply a good journalist and covered events objectively.

She even supports the idea that Russia will not change with the death of Putin and even with the victory of Ukraine. She says it is up to the Russians to change Russia and that she sees this way through revolution. He says that decolonization is necessary and essential and that the victory of Ukraine is crucial.

In general, Elena reflects very clearly on what happened, what cannot be changed, and what cannot be corrected. And to be honest, I did not expect that she would speak some kind of open propaganda at Yale University in a liberal society. This would be very reckless and detrimental to the sales of her book.

When you turn the questions to the future and some actions, I no longer see Elena, who said she would like to do more to prevent this war.

“I have faith in my country and love for it, a sense of belonging to people, and I hope that the country will change, Ukraine will win because if not, my country will die.”

Why don’t I see a call to action here?

Because there is no call to action.

I asked her how she sees her role in the processes of Russia’s transformation, in the revolution, in opposing the regime. She replied that after recovering her health, she plans to return to work as a journalist and to report on war. This is the same person who said in other interviews that just being a journalist is not enough and that you need to have a position and do more. I tried to understand if she had any plan, what a call to action in her book was, and how she would help the country she loves, but I have yet to get any answers. I’ve heard that she separates her activism from her journalism and has the expertise and connections to help those fighting against the regime inside Russia, but only at their request. Elena believes that it is unfair, “being in conditionally safe circumstances outside of Russia, to call people who risk everything inside the country to revolution.”

But what confused me the most was her assessment of the actions of the Russians. In one of the videos from previous presentations (at Columbia University), she says that Russians feel abandoned, that the government is against them, and the Western world cancels them (which I don’t think is true because I don’t see Russians canceling here, and sometimes even vice versa). And that people in Russia don’t support the war; they tolerate it. People have no choice because they live in poverty; that is why they see it as a choice to go to war and kill Ukrainians. A woman who lost a relative in the war has a choice between two narratives: that he was a hero and defender and that he died for nothing, just killing people. And Elena understands why the first narrative is more pleasant for the woman, and that woman chooses it.

After such words, the thought of a revolution in Russia becomes more and more ghostly. Until Russians do not feel responsible for their actions, until they understand that every action has a consequence, and until they stop tolerating war, there will be no revolution. Because the revolution is about freedom, and freedom is about making a decision and dealing with its consequences.

And for Ukrainians who lose friends, relatives, health, and homes in the war, it makes no difference whether the Russians support the war or simply tolerate it. Russians take part in it. Literally. Approximately 300,000 Russians paid with their lives for this.

One of the participants in the discussion raises the question that dehumanization is beginning, that Russians call Ukrainians “hohly, Ukronazi,” and Ukrainians call Russians “Orks” and don’t write russia with a capital letter. Elena says that during the war, people stop seeing the human being in each other, which is a protective mechanism. She says that the media and literature present war as something heroic, but in fact, “there is no heroic meaning in war; people are just killing and dying, and everything else is just an excuse to continue the war.”

I was nervous before the presentation because I expected to hear something outrageous that I would be forced to enter into a heated discussion. Doing so in an environment where you are a single warrior in the field is unpleasant.

But I didn’t hear anything new. I was not impressed by anything because I had already known it.

I have no sentiments for Elena, just as I have no sentiments for Russians in general. Elena is currently working in Meduza, for which I have neither sentiments nor trust because media experts regularly see pro-Kremlin and imperial narratives in this media. And yes, I read Elena’s reports from Kherson, Odesa, and Mykolaiv. I didn’t see anything not covered by Chernov, Maloletka, and many other Ukrainian and foreign journalists. But did see imperial words, for example, “Moldavia,” in a report from Mykolaiv. And there are sentimental dialogues between the “humane” Russian military and local residents of Kherson, which, once again, fuel the sympathy of the unfortunate Russians who “don’t know what they are doing.”

Elena believes it is wrong that Russians are reluctantly accepted in the Western world. For me, such hostility is logical because Russians are not aware that everything that happened and is happening in their country is the result of their life, their actions and inaction, their tolerance and support, their non-resistance, and their closed eyes on the crimes of the system. But the idea of supporting opposition Russians just because they are opposition is unproductive because this will not change anything until they, the Russians, start taking concrete steps to abandon their imperial narrative and change.

“Decolonization begins with love”, — says Mariam Naiem. I believe that it begins with a sense of responsibility for one’s life.

Also, Mariam Naiem says that she is ready to speak Russian if we are talking about the empire’s collapse. After this presentation, I believe it should be not only talks but an action plan and intention to implement it.

I really want to be wrong in my despair. And I will be glad to be wrong, though, if a “decolonization catharsis” (Lena Surzhko-Harned) and a revolution begins in Russia.

I do not consider Elena Kostyuchenko to be the worst Russian woman. She is probably better than my relatives in Russia. But she is useless for Ukraine’s victory and for me to feel safe at home. Because she fuels sympathy for the Russians who tolerate the war, who closed their eyes to all the invasions that Russia made around the world, and they began to “see things clearly” only when they were fought back – by the Ukrainian defense forces, by the Ukrainian people, by world sanctions.

Therefore, I do not think Elena Kostyuchenko’s public speeches help Ukraine win the war. With her narratives, she slows down the process of rethinking the great myth about Russia among foreigners. She cares that her “beloved country,” Russia, does not disappear. And here I don’t go on the same road with her.

Подякуй автору!

Сподобалась стаття? Mожеш подякувати автору гривнею.